Interview with Alyssa Ordu

Hello, and welcome to the Intrepid English podcast. My name is Lorraine, and today, I have a conversation for you. My friend, Alyssa, is a Diversity and Inclusion Consultant in London. And when I told Alyssa that we were creating a Diversity and Inclusion course, in the Intrepid English Academy, we had a lovely conversation about why diversity and inclusion are so important.

I asked her to join me on this podcast as an expert in this field, to break down these big topics so that our English learners and the listeners of this podcast can understand a little bit about what diversity and inclusion are, why they’re so important, and give you a little bit of language that you can use to increase your awareness and broaden your horizons in these essential areas. You can find links to all of the resources that Alyssa and I mentioned in this conversation at the bottom of this blog post.

The vocabulary in this episode is quite advanced. So I recommend reading this transcript as you listen. Make sure you write down any new words or phrases. And if you need any help or clarification, or you just want to discuss these topics further, please feel free to just send me a message in the Chatbox that you’ll find at the bottom right-hand corner of every screen on our website.

I hope you enjoy today’s episode.

Lorraine: Hi, Alyssa. How are you today?

Alyssa: I’m very well, thank you, Lori. How are you?

L: I’m really well, thanks. And I’m really excited to speak to you because, well, you’ve just got so much to say that I want to hear. So I’m really excited. You’re actually in a hotel room in Berlin at the moment, aren’t you?

A: Yes.

L: So why don’t you start by introducing yourself for everybody?

A: Of course. Hello. My name is Alyssa. And I’m a Diversity and Inclusion Consultant.

L: And how did you get into this job, Alyssa?

A: Good question. And I think for me to answer that it might make sense to take it, take it back a little bit before I maybe even joined the world of work. So I grew up in a vibrational home. My mum is from a small town in south Wales. And my dad is from a village in southeast Nigeria. But they met in a disco in London. So go figure. Nobody has better meeting stories than 70s parents. And they raised us, me and my two siblings around the world. So we grew up in the Philippines and in the States. And then later, Indonesia, and also in the UK. So I think I’ve always had a bit of a fascination or penchant for culture, right? For travel and learning about different people and their experiences. And something I noticed with all of these moves in this kind of ‘multi-culti’ upbringing, as it were, was that so many of our social problems are similar. Our circumstances might be different, right, our levels of access and infrastructure. But that really more connects us than separates us. And that a lot of the key things that I notice, there being collective struggles with centre around things like gender, centre around things like race. So I think I was always a little bit interested in, yeah, how people work and why we do the things we do and how those things are done to some people in different ways and, or unevenly, or unequally, if you will. And then fast-forwarding to me being at uni, and studying psychology, in gender and international development. So obviously, the fascination with these themes continued. And then I joined the world of work. And one of my first main jobs, big jobs, I suppose, was in HR. And that was something I really, really enjoyed. Having the power to hire a broader range of people, a diverse range of people was something that I found really interesting. And from there, I did a little bit of a pivot into working in marketing and communication, but mostly in the tech sector, and within that within software companies, and something I noticed, which you may not be surprised to hear was that, in that sector, there weren’t a lot of people who look like me. I was oftentimes the only woman in the room or woman in the company, and oftentimes the only person of colour as well. And thinking, you could say intersectionally. I was experiencing both of those things at the same time, right? So if we think about intersectionality, is how our identity or experience in one area can be compounded by our identity, or experience in another area. So I was feeling my otherness, I suppose, in relation to being a woman, but also in relation to my race, too. And those are just two of my intersections, obviously, we will have many different ones. So selfishly, the short answer is, the reason why I got into ‘diversity and inclusion’ or ‘people in culture’ or whatever this field of work is going to be called in a couple of years time is, I was really determined to change things and prove that the reason why there weren’t more people like me and in the sector and in the space wasn’t because we aren’t good enough, wasn’t because we can’t do these jobs, it was just because we faced unique barriers to entry and accessing those jobs. So that led me to pivot again, I suppose, and start doing training and designing workshops, primarily in the technology sector, but not exclusively. To help teams and help the C-suite understand, you know, what’s really getting in the way of building a truly inclusive workforce for us. And I think understanding our bias biases, plural is a really powerful way to start.

L: Wow, thank you for that, I have so many questions that I want to ask you.

A: Ask away!

L: One of the things that really sort of stood out to me and what you were saying there was related to the concept of barriers. And I have experienced confusion among my students about barriers because it’s a very strange area to discuss: If you are benefiting from privilege of some kind, for example, if you’re a man, or if you’re a white person, or particularly a white man, then you might not be aware of the barriers that exist for other people, because those doors are open to you. And often you’re only aware of the doors which are closed to you. But we require people with that privilege to use it to open the doors for people who do not have it. So trying to start from a very beginning position of ‘This is what a barrier is, and these are the people who traditionally have experienced these barriers and come up against them’. This is the first step, I think in explaining why diversity and inclusion is something which benefits everybody, not just the people who have traditionally been held back. But everybody because all teams are better, all departments, all companies are improved by having a diverse workforce with people from a range of backgrounds, a range of experiences, and like you said, different intersections of society. Because, let’s take, for example, gender, you know, a marketing team, which employs only white men, they are missing out massively on having a diverse team because they’re going to try and market to everybody, but they only see things through the filter of white men. So that immediately puts them at a disadvantage in their roles, right? So yeah, from the point of view, as someone who’s worked in HR, and you’ve dealt with diversity in many different kinds of companies, how would you define ‘barriers’? And how can we start to remove them for those around us who are held back by them?

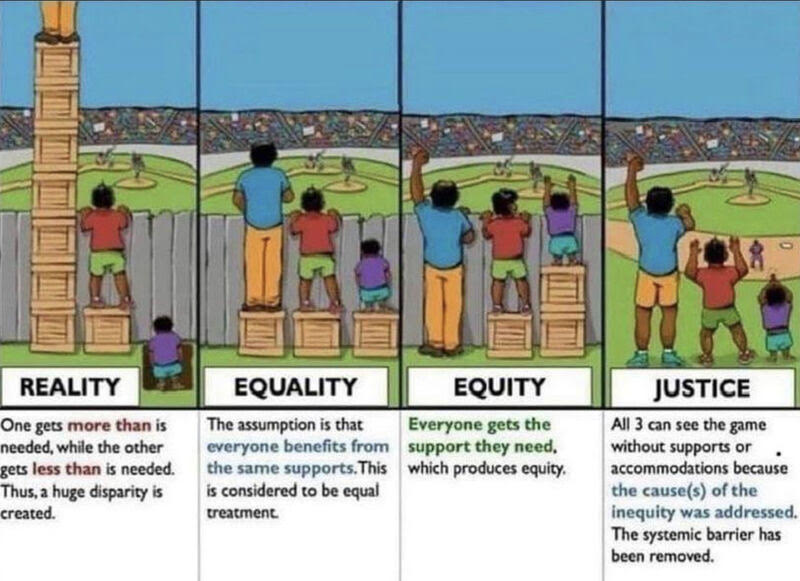

A: Well, I think, in case we have any visual learners on the call, I’ll try to explain it in relation to a visual metaphor. It’s a little funny in an audio format, but here we are working across the senses. So I recently saw a cartoon, I think a couple of different artists have re-created it. But it really, really resonated with me and some people who were maybe working in this space might already be familiar with it. But I think it’s a useful reference point. And in this comic in this drawing, it lays out equality versus equity versus justice.

So when they say equality in the picture, it’s basically several people who in front of them have a wall. And beyond that wall is a game of sorts. So just imagine a ball game, say baseball, right? So in order to make the people that look different, you know, they have different abilities, different, they have different colours, they have different heights, just different forms of appearance, in order to make them on equal footing. Each one has a block placed underneath their feet. And each of those blocks for those three people is the same height. Right, so now they’ve got this fence in front of them. And they’re all standing on a block that’s the same level. But what that does, right, if we think about that, in relation to equality, or giving everybody equal access to things, which has some benefit, but it doesn’t account for things like privilege, or things like oppression. So now the tallest person who had the same size block as the smallest person, or the person in the wheelchair, can now just have an even better view of the ballgame, even though they could already see. And some of the people that have the same size blog might still not be able to see anything or might have a partial view.

So if we think about equity, instead of giving each person the same-sized block, what we would do is give them the size of block, they need to see over the wall, which might mean that the tallest person doesn’t need to block at all, it might mean that the child or the person in a wheelchair might be the largest block, just as one example. But then if we start thinking about justice, and this is the final piece of the pie in this image, that would be us taking the wall down entirely. So everybody just sees from their natural vantage point, if indeed they have the ability to see. So I think when we think about barriers, that’s kind of the approach or energy I take towards trying to understanding them; that not everybody has the same barriers. And I might not understand everybody’s barriers yet. So this is something I bring up a lot in my work. And I think some people see it as a strength, some people might see it as a weakness, and for those who feel the latter might not be people I work with. But I think I’m still on a learning journey with all of this stuff, our culture is changing so fast. I know more today than I knew yesterday, and I now know enough to think, ‘God, and there’s a hell of a lot more, I have to learn’.

So just wanted to say that what I see as barriers to entry are things that stop us from being able to do what we want to do. So thinking in the context of hiring, for example, I know that in recruitment, we can kind of there’s a bit more black and white versions of these things. But there’s so many studies showing us that even just the name you have when you apply to a company or to an organisation can influence your likelihood of being accepted. And how that changes even within different ethnic groups and nationalities. I was reading one study by the British Centre for Social Investigation, which was run a couple of years ago, within their own organisation, they sent out about like 6000, CVs for different job descriptions. And what they would do is all of the CVs would be the same. So the people applying would be, the fake people applying, will be just as fabulous, you know, going to fancy unis, or what have you. But the only thing that would change would be a name on the application. So they did this across things like gender, but also things like ethnicity. And they found that just as one of the examples, they found that people with Nigerian sounding names, or South Asian sounding names here in the UK, had to send out 60% more applications, just to get a response, not even necessarily to get a job interview. And this study wasn’t done 100 years ago, or, you know, this is recent.

And we’re seeing this time and time again. So I know that some of the barriers that we face are in relation to things like or gender or names. And I think part of that comes from the fact that if we’re not accustomed to having certain people in roles, then oftentimes we’re not accustomed to supporting other people into those roles. So something you said earlier that really resonated with me around privilege was that and there’s a saying, I think it was Professor Kimmel that said this, “Privilege is invisible to those who have it”. Or the more that we have it, the less able to notice it we are those things that are just normal for us, or not a problem for us, doesn’t mean they’re not a problem for anybody else. Right? So I think that’s what we have to sort of be conscious of when we think of those barriers, but also remembering that we don’t have to look at privilege as a negative thing. I feel like I see so many memes and so many conversations of people saying like, I feel like I can’t speak up because I’m in this group blablabla. And it’s just like we’re just running around, chasing our tails, you know, hating on each other instead of coming together to realise: divided we fall and it’s only really together that we stand. As soon as we start, like unleashing the power of using a privilege as a force for good, to me, that’s where so many exciting opportunities lie. And then things like barriers become childsplay, because the more of us that are trying to kick the ceilings down, the faster the glass will break, and we’ll see, you know, beautiful skies ahead.

L: Oh, that’s, that’s lovely and super positive. because quite often, you can really get bogged down in, in just how much work there is to do. And it can get really quite depressing, sometimes, can’t it? But I’m glad that you finish that off with a really positive note that because not that we need to sugarcoat this difficult topic at all. But you know, from, from the point of view, from our students anyway, this course came about because a couple of years ago, I had a conversation with a student who was avoiding one of his coworkers who was a trans man, because, yeah, he just, he just didn’t know what to say. And he desperately didn’t want to offend him. He didn’t know what to say, and he didn’t even know whether he could ask for this person’s pronouns. And I realised that we need to meet our students where they are. Depending on their culture, depending on the you know, the society that they live in, sometimes they’re really these, these topics are not discussed at all. And it seems quite intimidating. And there is so much to do, and there is so, so much uncertainty, and each person’s experience is different. So, you know, there are definitely opportunities, in all conversations to accidentally say something wrong, you know, and it’s quite, quite scary for a lot of people, especially in a second language. But yeah, we really want to meet them where they are, and show them that actually, by making an effort, and just generally being kind and inclusive, we can all work towards a better, more egalitarian society, which is so important when you’re working in an international company, and you’re working with people from all different backgrounds, all different experiences, you need to, you need to be at least aware of what not to say. So that you can, you can start to, you know, allow everybody to essentially do their job well, because that’s what we’re all at work to do, you know. And I just wanted to mention as well, actually, that cartoon that you described, that cartoon is actually in the course, I saw that and I was like, This is so brilliantly explained in this lovely cartoon. So yeah, we’ve actually embedded that in one of the lessons right at the beginning, actually. So thank you. That’s really cool that you, you mentioned that. You mentioned something earlier, Alyssa, which was really interesting to me, you mentioned that we all have biases, would you be able to explain or give an example of what a bias is, and why it’s actually the point is not to deny that you have a bias, but we all have them. And that by appreciating that biases are everywhere, how we can then start to move forward from how harmful they can be, would you be able to give us a bit of background about about biases and what they are?

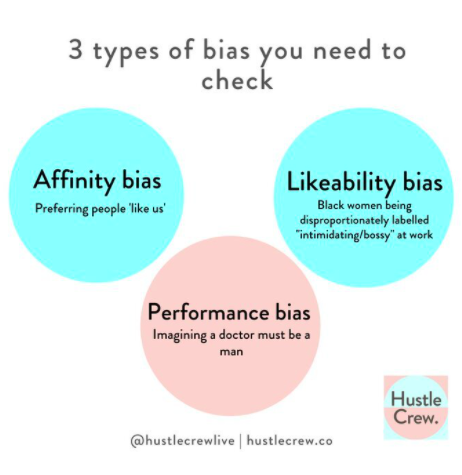

A: Yeah, absolutely. So I think one bias that I see a lot is around things that we have in common. So one thing I’ve notice is what we kind of phrase is ‘affinity biases’. So you might say I have an affinity for a certain thing, I like a certain thing, right, or I’m in a certain group.

And in terms of how I see this playing out, is I’ve noticed that before I sort of started working for myself, and you know, doing consulting across companies, I was doing more in house type roles. And whenever I was in interviewing rooms, I would, you know, look up the person that was going to be interviewing me (a little light stalking on LinkedIn) and kind of get a sense of them, and then maybe touch on things I know about them and build rapport quickly. But I sometimes found this a little bit tricky to do, especially if the people interviewing me, were really, really, really different from me, for example, culturally, right? Maybe they have a different accent to me. People are always pulling me up on having a funky accent probably from all of these moves or, you know, maybe they lived in a different place. Maybe they’re also a different gender, maybe they’re also a different culture. So one of the things I would often try to have an affinity with them was around school. And it occurred to me recently when I was looking through my CV that a large percentage of CEOs I’ve worked with, went to the same university as me. And I realised this isn’t a coincidence, right? I mean, London School of Economics, flashy, flashy, snobby school, it helps when you name drop it, but some of those jobs I got, because, you know, they actually those companies release their job adverts to that network. You know, oftentimes if there’s a founder that comes from a certain community or comes from a certain school or certain MBA programme, whatever it is, especially, I think, in tech, where there are some companies where, you know, everybody went to Stanford or everybody went to MIT, and it can be like, so microscopically specific. But yeah, so I realised that one or two of the jobs I had gotten were because they exclusively advertise to that network. So it wasn’t like I found the job by chance. And even for things for roles that I found outside of that network, I was always very careful to bring up the one affinity, I felt like I had in common with the interviewer or with the CEO, like, “Oh, I see, we both went to…” and I tried to like trump up some stories about my time there, even if we were there in different decades, so try to have something in common with this person who’s grown up in a life so different from mine. And I remember talking to other friends of mine, about like, what they do, and they were like, “Oh, well, I tend to have so many things in common with the people that interview me”. And I thought about it because, of course in society, due to patriarchy, among other things, men are in a greater position of power. And particularly in our tech workforce, white men are in a greater position of power. And most people interviewing me were like that, and I wasn’t. So if we start thinking about bias in relation to these affinities, I think that can be an easy entry point for us even just reflecting on the bosses you’ve had?

L: Absolutely.

A: Did they all look like you? Or did some of them look like you even looking at your friends? The top couple of people in your WhatsApp or your whole phonebook or your LinkedIn community? Do most people there tend to look like you?

L: Absolutely.

A: Do they tend to have certain more in common with you than they don’t? And then imagine how different that experience might be for me, or somebody different from me kind of coming into your same sector, who can’t lean on those same, those same cultural norms or can’t lean on those same commonalities. So I think that for me, that’s kind of the simplest way to look at a bias. It’s not always coming from a bad place, which is funny thing to say, these are things that we, we do so naturally, that we that’s to your point, you know, about them being everywhere, we almost don’t realise that we’re that we’re doing it even just thinking about who you sit next to, on the train, do you only sit next to the darkest person, if it’s the last seat left? I mean, this is just transport. But I see it all the time people making these decisions; who do we see as being more dangerous? Who are we more likely to try to serve first in a shop, right? Who are even more comfortable with? Typically, it’s people that have something in common with us: an affinity with us, or are more like us, and that people that are less like us, we oftentimes are more likely to avoid and even dislike. So when we think about recruitment, and the way that that plays out, it most people that have hiring power, look a certain way, and spend more time with people that look like them, then it’s kind of no surprise why we have certain barriers to entry like it being harder for other people to access those jobs, when they’re kind of already being judged from the get-go. Something I’ve seen that’s kind of interesting in this space. In terms of recruitment, specifically, as there’s now a series of different pieces of tech, you can use, like platforms and programmes that some companies are embedding to strip out certain biases, so like to remove the name of candidates, so you don’t know their gender or ethnic background, you know, not asking questions about gender or things like that, stripping out things like universities, because we know that there’s also unequal access to universities, let alone elite education. But something i thought was interesting when with some of the companies I’ve worked with, who say that they’re using these techniques, and almost like proving to me like, “Hey, we’re doing the thing, like, isn’t that good?” And I thought, well, I mean, it amazes me that we have to make these solutions in the first place. And part of me was like, well, yeah, that’s, that’s good. If it’s helping you get more diversity in the door. But for me, diversity is one piece of it, right? That’s not mutually inclusive, or synonymous with inclusion, definitely not belonging. Because I wonder if we have to use systems like this, in order to, for example, hire Black women, what’s going to happen to those people when they actually enter?

L: Yes, exactly.

A: So that’s why I think we have to work on these biases, whether we’re putting a programme on top of something to try to like, funnel it out in the beginning of the pipeline, the beginning of the chain, we also have to be doing the work. And that’s learning about things like biases, learning how to understand and then utilise our privilege. Otherwise, I think we’re just going to keep coming up against the same problems.

L: Yeah. 100%! There’s so much to comment about that there. Thank you so much, Alyssa for that really, really clear explanation and and way of approaching it which isn’t so, so shameful because quite often we hear about biases in in a shameful way because many, many are. But for example, I want to bring up two recent examples that I’ve encountered. So one of the TED talks that we have embedded in the course, is by a wonderful woman who, who deals with biases. She’s a very accomplished Black woman. And she was explaining a story where she was on an aeroplane, and travelling to an opportunity to be a keynote speaker about biases. And the aeroplane hit some turbulence. And the pilot’s voice came over the loudspeaker. And it was a woman saying, “Not to worry, we’ve hit some turbulence, and we’ll be going through it soon”. And this lady, the TED talker, she said that her initial reaction was, “Oh, my God, it’s a woman, I hope she can drive”. She wanted to just start her TED Talk with that because she wanted to show that it was, it was innate, in so many of us, we have these biases. And the first, the first step in the journey is to recognise that and to recognise that we all have them, and then to try and move past them as well. But earlier on, you mentioned intersectionality. So for for those people who who aren’t aware of that, we’ve got a section in the course about intersectionality. But to boil it down to its its most basic kind of form, it’s the understanding that we are all parts of many different communities. Well, you know, most of us are working with people from a range of different cultures, and, you know, nationalities, languages, sexual orientations, religions, you know, races, genders, the list goes on. And the the knowledge that we are members of different communities. As the world is opening up, and we’re becoming more of a sort of Global Village, this is this is such an essential thing to to recognise. until the point at which it doesn’t have to be an issue anymore. Until the point at which people are welcomed and people belonging in any space, no matter what the communities they come from, or they they identify as, this really is important.

And I wanted to quickly bring up the intersectionality between… so we’ve talked about race and gender, especially in tech fields, but to your point about finding an affinity with your interviewers based on having been to the London School of Economics, I saw a wonderful post on LinkedIn a few days ago, where the the poster said, we are doing ourselves an injustice if we don’t talk about socio economic background. So for those of you who don’t know, at the beginning of this year, we had our first black Secretary of State here in Britain. And this is this was a moment of celebration. Wonderful, that’s great. But dig a little deeper. And this particular person had been to Cambridge and Oxford, he had a scholarship, a Kennedy scholarship at Harvard, he went to Eton, like so many of the conservative MPs that we have in our cabinet. And there has to be a moment where you acknowledge that this particular person has done great things in order to get to where he is. And it’s a shame that it’s only he’s only the first Black Secretary of State here in Britain, especially considering our history of multiculturalism. But, you know, he’s still benefited from a lot of privilege. His his parents were extremely wealthy / are extremely wealthy; I’m not sure if they’re still alive. And he, he has been surrounded by money and people with money. While we need to celebrate this milestone, and you know, it’s a long time coming. It’s important to recognise that he still does benefit from privilege. And socio economic background is something that isn’t talked about that much, mainly because it’s, you know, it’s such a… it’s interesting how it’s such a goal for so many of us to have social mobility and to improve the quality of their lives, yet, there’s so much shame that comes along with you know, coming from an underprivileged background.

So dropping those barriers is so important, giving access to education giving access to energy. You know, that’s, that’s something which is really far behind in a lot of areas of the world. These fields are all combined, they’re all interconnected. So dipping your toe in a little bit seems quite scary to begin with. But once you actually start to figure out that everything is connected, the issues with climate change are connected to issues with racism and gender inequality. You know, COVID-19, is connected to so many other issues. So this is there’s no one in the in the world that is not touched, even indirectly, by these issues. And that’s why it’s so important to just start to learn, and to feel, especially with Intrepid English, that wherever you are on the journey, even if you’re right at the beginning, the important thing is that you are trying to learn. And Intrepid English is a judgement free place where you can move forward with your understanding. And it’s incredibly satisfying and incredibly fulfilling when you realise that these big topics, they’re just a conversation away from having a little bit of understanding about them, essentially.

A: Absolutely. Just a conversation away from a little bit of understanding. Yeah, I love that.

L: Going right back to the beginning, where you talk to us about where you come from being in a biracial household, your family comes from different continents. I’d love to know about that. And how specifically have languages informed who you are now in your identity

A: Sure! Well, at home, we were just a typical Anglophone home. My dad never spoke to me in his language, which, now that I’m older, and hopefully a little bit wiser, I feel like is a great, great shame. And my mom did speak to me and her language. So she’s South Walian, and a lot of us don’t necessarily speak Welsh, so nor does she and nor does our family over there. So yeah, we were always just speaking English at home. But I think because of the environments they raised us in like, namely, like our access to travel, like our mobility in that way, and living in different countries, I was always around a lot of different languages. Part of it was access. But when I hear people talking in different languages, like my ears, almost like zero in on it, and yeah, and I think also from living in the Philippines, where the language is quite similar to Spanish, there’s a lot of crossover. I mean, the Spanish conquered for, gosh, any history buffs on the line will catch me here, I think about 500 years, colonising as it were. So the language is very similar. So in Tagalog, the language a lot of people speak in the Philippines, to say, ‘How are you?’ you would say, like “Kamusta ka?”, whereas in Spanish, it’s “Cómo estás?”, so it’s, you know, very similar. So I kind of heard a lot of that growing up. And I think that bent my ears to understanding or being more open to or more used to Spanish style pronunciation. So then, when I was in school in the States, and I had access to Spanish lessons, a Spanish class that I took for a few years, it just kind of became easier for me to follow it. And I remember, I had this one particular teacher who was always really surprised at how strong my accent was, and how well I was able to understand, but then she was like, a little bit surprised with them. Like some of the limitations I had in writing, or with certain tenses, she was like, “But if you can understand this, you must know this!” So I kind of jumped ahead and got put into a higher class, but some of the basics I didn’t have, because I think sometimes it’s like learning by ear. You know, people say that with piano, you’re learning by ear versus kind of growing up with the theory and the notes and kind of all that. And then once for me, I was able to get a pretty good standing with with Spanish it made it a lot easier for me to understand French when my parents moved to Tunisia and I kind of had two options there like pick up some French or pick up some Arabic. I was less successful with Arabic I was more successful with French it was a little bit easier for me. And then I kind of feel like from their languages like Portuguese and Italian kind of then don’t seem so dissimilar.

So I think… Yeah, that would be my my point of encouragement or advice, a suggestion to people that are trying to pick up different languages is maybe also make it easy on yourself. I mean, definitely follow your interests. If you’re interested in something and curious, it’s gonna… your rate of uptake will be much improved because you have the drive, the passion, but also if you’re interested in languages that are similar that I can maybe be a good place to start, because I’ve definitely benefited from that, I suppose you’d call them like Romance languages or Latin languages where there are cognates that are the same. The root of the word is so similar that then, you know, I find myself travelling in a country where there’s another romance language. And I almost feel like I’m just kind of merging it together. Like, just adding an additive slightly different ending that sounds right. And I think for me language like, conversations about diversity, conversations about inclusion, I would just advise everyone to try, right the only way that we never fail as if we never, ever, ever try, and nobody had Intrepid English isn’t a trier, otherwise, they wouldn’t be there. So that would be my suggestion is: you’re going to make mistakes. And actually, the more you do, the harder you try, the more mistakes you will make, but they’ll be different ones. And you’ll you’ll start to learn faster. And that’s what I do with languages I just throw myself in. And I’m willing for people to laugh at me if I do the wrong thing. But as they laughing, they’re also helping correct me and helping me fine tune. I wouldn’t have that opportunity if I didn’t exercise that effort and that curiosity.

L: Great. It seems like this point comes up no matter who I speak to. Anyone who’s learned another language, and quite often people who haven’t even learned another language, but are genuinely learners. They are lifelong learners. They like to learn things, and they’re curious, they always talk about the importance of making mistakes. It’s so heartbreaking, though to make a mistake, especially when people laugh at you. It’s like this essential part of being better at anything is just so difficult to actually take. But I think it’s like anything, the more you do it, the better you get at it.

A: I also feel like it’s a silver lining. Because if you you can look at it like, “Oh, I don’t want people to laugh at me”. Who does? But also, the more you’re learning through their laughter like, the more you’re able to make a joke in that language. And then they’re laughing with you in the way that you want. So it’s like, it kind of goes both ways. It doesn’t always have to be a negative. It’s like, actually, it’s a gift that people are engaging with you and helping you be more successful in that language. That’s just, that’s lowering the barriers to entry there’s you being able to better communicate with more people. And for me, I feel like that’s so much of being alive. And that surprises me why I’ve never done podcasting before because clearly I like conversations! But yeah, the more we can kind of speak different languages, the more we can understand each other, the better able to connect and have fun together we are. So, that’ kind of my angle.

L: Absolutely. 100%! Yeah, in my most recent University module, those studying I did an essay about the different types of English there’s no longer English, the language singular; there are so many of them. There are just a huge

A: Pidgin

L: Yeah, all of that, you know, Creoles, everything from, for example, German and English kind of combination words are called ‘Denglish’ for Deutsch.

A: Ja! Das ist ‘Denglish’!

L: Have you been speaking English in Berlin?

A: Yeah. Because ‘meine Deutsch ist nicht gut’. So it’s more like ‘Denglish’.

L: You have the accent though!

A: Vielen Dank! I’m trying. I’m trying to understand the jokes.

L: You know, I was talking to our newest teacher, she’s based in South Africa. She is really so lovely. And for such a young person, she’s really thoroughly deeply aware of this… She’s studying Politics and World History at Nelson Mandela University, so she’s got a lot to teach me. So we often get right into conversations. She said to me, “Lorraine, I’m struggling a little bit with the question of teaching English as a language, specifically in light of the colonial past, and I want to know what you think about it.” We had a really interesting conversation about this. And luckily, she had the time to read the essay, I said, “Look, I’ve written an essay about this, which is always going to be more articulate than me trying to describe how I feel about it. But if you’re interested, you can read it.” This is the kind of thing she likes to do. So she, she went away and read the 3000 word essay. And she said that it really helped her to understand, to sort of negotiate these two opposing ideas of teaching English in order to empower people to improve the quality of their lives, whilst recognising that the language of English that we we teach, it has a very dark past. And we wouldn’t want to ignore that. But it’s something that a lot of English schools don’t even think about. Don’t even address but if you are taking English lessons and you live in a country which was previously colonised there may be very ingrained conflict between your culture and your language, and English. And that’s perpetuated through the education system in many countries, because let’s take Hong Kong, for example. You have English-medium schools, and you have Cantonese medium schools. And it seems like that is a point where socio-economic privilege starts the divergence in a lot of people’s lives. So if you can’t afford to go to an English-medium school, that it’s almost as if the Cantonese medium schools are, you know, an inferior choice in many cases, or that’s the way it’s perceived. And that can be the start of this privilege, these blocks that we can stand on in order to give us a boost in life. So I think it is really important that we address that. And one of many answers to this question is that language policies in countries are developed, not only to put English in in a position of superiority, but to recognise the value of multiculturalism, multilingualism, and even hybrid languages with English, so that rather than ‘the Queen’s English’, that is often taught by a lot of English schools, that’s the I don’t believe that is the the ideal, that is not the goal. I believe that one of many goals should be for English to exist, as well as and in combination with and in concert with other languages, because all of them benefit us just in the way that a diverse team benefits everyone. Diverse societies benefit everyone. And I think that’s a really important thing to address.

A: Yeah, I love that. I think, kind of querying the boundaries of what English is or can be, and how it can be taught is immensely valuable. But I also think, you know, maybe it’s a call to action for people that already do speak English, or have English as a first language, to also try speaking other languages and maybe speaking languages in the global south, as well. Because I think, interesting things can happen that way, too, when it’s not just everyone trying to communicate with this one group, or this one perceived elite group, as you pointed out, like with the differentiations of language schools, you know, Cantonese or Fukien or Mandarin versus English. And like, what had the bearing that might have your access to those different schools in relation to class or to, you know, money. But yeah, I think the world would be an even more exciting place, if we started to see more multilingualism happening, and not just people feeling like they have to learn English, or people feeling like just having English is enough, and kind of resting on their laurels. But I know, languages are easier and harder for some people to learn. But I think there’s so many, so many ways that language is becoming easier to learn. And there’s also just the old fashioned way, which is my favourite, which is just chatting to people speak a different language and having some laughs along the way, whether that’s due to my bad pronunciation, or due to, you know, the lame dad jokes I make in their language, because like, my level might be so low, but I’m like, hey, it still counts, even if it’s like a ‘knock knock’ joke. Because I think that so much of our culture is trapped in language. So the more we can kind of connect on that level, kind of gives you a bit of a deeper view…

L: Yeah, more tolerance.

A: Learn about their future, but also, you know, their past.

L: Yeah. I mean, barely a week goes by that a student doesn’t teach me a really interesting word in their native language that I try to adopt. because quite often, there’ll be a concept in another language that you would have to describe with a whole sentence in English.

A: Yeah.

L: And I love learning those words!

A: Me too! Isn’t it great? Yeah, I was reading. I’m trying to remember where it was. It might have been on the guardian. But it was an article that was about the words and that since the last two years that have been added, I think I’ve got Germany on the brain because I’m in Berlin just now. It was about the new words that’ve been added to the German dictionary since Corona, in relation to Corona times. So like one of them was called ‘Coronaangst’. Like ‘Corona’ ‘angst’, like anxiety, yeah, the anxiety around it. Around going out, you know, around being vaccinated, not being vaccinated. And there was Another one around, like the foot handshake, like the ways in which we’re trying to say hi to people on the street more safely, or even the people that you have ‘Kuschelkontakt’, so like ‘Kuschel’ is… so and Welsh we would say, ‘cwtsh’, but just ‘cuddle’ in English. And then ‘kontact’ like ‘contact’. So the people that are in your immediate circle, like maybe a parent, or like that one neighbour who you can go to for touch contact who won’t look at you funny if you try to hold them. And it just I thought the whole thing tickled me so much because I mean, language is evolving constantly, every day, right? I mean, languages are dying out languages are being reinvented. Languages say a lot about our culture and how we connect to people. So I’m always curious about how much more I can learn in someone’s language, even if it’s just a little bit to sort of get my foot in the door. Because I think it definitely is… it makes it easier to build rapport. If somebody knows you’re trying to see from a more similar vantage point as them and language, I think, is a way that we can build that. Yeah, it’s such a simple way, isn’t it? When we’re travelling abroad, to just learn a few words of a language and be prepared that if you pronounce it badly, that they have a bit of a giggle because it’s funny, sometimes when someone pronounces something really badly. It’s funny, don’t take yourself too seriously. I mean, this is just a simple thing to do. We’ve all got access to Google, we can all learn a few basic phrases of the country that we’re going to. And it’s amazing how many doors that unlocks, you know, how many people who might have approached the conversation like, “Urgh, it’s another tourist”, you know, you try and roll out some of those basic phrases, mispronounced for comedic value, and all of a sudden, you’ve got a new best friend.

L: Yeah, it’s just such a simple way of connecting.

A: Yeah, it shows you’re up for making an effort. And I think, in particular, for people like us, that our native tongue is such a dominant language that’s, you know, very much has a colonial past tied up with it. We can kind of come across as quite like entitled. If we’re just like, doing the thing that I’ve definitely seen many Brits abroad do where they just sort of say whatever they’re saying… louder. Yeah, even just saying a couple of words, even if you then switch into English, people’s likelihood of being more responsive to you, and you may be getting closer to whatever the thing you want is… finding out what the closest Metro is, or if you’re on the right street, is more likely to happen. When you already kind of put the ball in their court a little bit and show like, “Hey, I’m trying here”, as opposed to “I’m expecting you to try for me because I’m on some high horse with expecting everybody should speak my language and speak it like I do”. But I think that kind of tide is changing, hopefully, a little bit.

L: Yeah, I think ironically, as well, in my experience, if you are making an effort to speak somebody else’s language, they quite often because my native language is English, they will think this is an opportunity for me to practice my English but because you’ve broken the ice by trying to speak their language a little bit. And then they’ll maybe, maybe be a bit patient with you and then say, “Is English, your native language”. And then when you say, yeah, then they have a moment of thinking “Great, I can practise” and you have a moment of “Thank goodness for that because that was all I knew in that language”, it actually works a lot better. Whereas if you approach them in English, often they will just shut down.

A: People oftentimes just walk away. Yeah, I know what you mean, though, about the, “Thank god ’cause I’ve just used up the seven words. I know that language”. Little did they know!

L: One thing you mentioned earlier about hiring that was really interesting to me. I’ve been getting quite into LinkedIn lately. When I first joined it years ago, it was very boring and bland. But recently, I’ve made a conscious effort to follow people who are a bit different, you know, a bit diverse, a bit unusual. For example, one of my favourite people to follow on LinkedIn is Lea Turner. She’s covered in tattoos. She is what many people might think is the ‘opposite of professional’. I can hear you typing away there. Yeah, you friend her. She’s amazing. It’s become a much different place because I have consciously curated my network in a much more sort of diverse way. It’s not been a passive experience as it was before. And that has proven to, you know, result in a very bland network. I didn’t just follow the algorithm, I’ve gone in there and you know, followed people who I think really have something new to say. You can call them thought leaders, I don’t know. But a lot of the time, they’re people who don’t look like me, are not in the same step of their journey to mine. People from, of course, a lot of different cultures and countries, but people who inspire me in one way or another, and who I might have the opportunity to learn from, essentially. But still, when I was hiring for the latest English teacher, it was so frustrating to me, I was looking for quite a while. We are diverse in terms of age, in terms of native and non-native speakers, we’ve got several members of the LGBTQ+ community in our small team, but we were not racially diverse enough. So it was a goal of mine to hire a person of colour for our team. And it was really frustrating to me that it wasn’t as easy as it was to find a white, British English teacher. I was quite frustrated by it. And I said to the other teachers, you know, I want you all to go out into your network. And I want you to find great English teachers, specifically an English teacher of colour. And like you said earlier, there isn’t a lack of amazing English teachers of colour. There, isn’t! My bubble was really white. It’s not a pipeline problem. And I had to step outside of that. It’s always an interesting learning curve for me, and I’d love to hear your thoughts about that. Well, firstly, I’m just really happy to hear about it.

A: I love that you’re kind of, you mentioned something earlier about there being people that are continual learners. And that spirit definitely exists within you that you keep raising the bar and moving the goalposts and trying to do more. So I’m just happy to hear it. But in terms of my thoughts on that, I would suggest doing, basically what you just said, trying to think about, you know, whether it’s diversifying the content you consume, or the spaces that you play in, as well. So I think for a lot of people in the UK, maybe people are reading newspapers, like I don’t know, BBC, maybe The Telegraph, Guardian, or maybe tabloids, like the Daily Mail, even. But I think we forget that we have other options out there, we can also read old Black news publications, like the Root, for example, or feminist publications like, Jezebel, I’m just throwing a few out there. And I think that we’re so lucky to live in the internet generation time, we have so much access, and that can be kind of overwhelming. But at the same time, sometimes we can do a little bit a little bit more, and kind of shout outs to places like Netflix and Prime that are just making it so much easier to like give us matches to optimise for our searching intent. And then I use it all the time using keywords like, you know, ‘Black directors’, or ‘South Asian films’, or whatever it might be or like across languages too. So I think it’s becoming so much easier for us to engage with different people. But I think it’s like: ‘Are we challenging ourselves to do more of that?’ And also remembering that we can learn about people, who are different from us from people like ourselves, or we can learn about those people from them. And that is a very different thing, right? Because oftentimes, if it’s between ‘us’ or ‘them’, like ‘us’ is usually positioned as being above ‘them’. So that would be my kind of recommendation to people, whether you’re listening to queer podcasts, or searching for queer podcasts on Spotify, or whatever it is you might be doing, just remember that there are so many different stories and experiences out there. But are you taking the time and making the effort to learn about them, from the horse’s mouth from those people themselves, and I think recruitment is much the same, rather than thinking about it as a ‘pipeline issue’, as a problem in that sense, because you can’t immediately see it. Because as you mentioned, it’s maybe not immediately within your bubble, jump into different bubbles. Talk to people that are in those bubbles, and also pay people for what you need! Something that I see happening a lot, both personally, which I’ve experienced firsthand, and also by a lot of other people of colour that work in my industry, is that oftentimes people just sort of come to us for free recruitment, like, “Oh, you must know lots of colourful people, like just do the thing. Just like put this out on your LinkedIn”. Well, if the job is worth doing, it’s also worth getting paid for. A lot of people use recruitment firms. Are you looking to recruit in diverse communities like I don’t know, people of colour in tech? Paying them to put an ad up there or paying Hustle Crew, another community, a super diverse community. You know, are you finding spaces like that? Companies that are doing the thing that you want, and paying them for that access, paying them for their talent, just as you would more traditionally, let’s say white companies like I don’t want I don’t want to name them, then it sounds bad. But there are many platforms that we that many companies pay, and there’s lots of recruitment that isn’t always diverse that we, you know, people are getting that, that rate where as soon as somebody is hired in, they get part of the first month’s salary or whatever like that. So I would say whatever your normal recruitment processes. And you don’t have to necessarily reinvent the wheel. But if you want different results, you do need to start doing different things. And that might mean jumping in and getting dirty in a different sandbox than you normally play with. Whether that’s specifically looking at more women like, Lesbians Who Tech, Black Girls Code, whatever kind of areas you’re trying to optimise for, and be more inclusive of, I’d say Go. Go to the communities they’ve, they’ve been doing it longer than you. Get their help, but also pay for it.

L: Pay for it. Yeah. And there’s a couple of things that I wanted to mention there as well. So one, it’s not hard. It’s not hard to find diverse companies out there who work specifically, you know, in that field, it’s not hard you all you need to do is Google it.

A: Or listen to this podcast and Google these.

L: Exactly. I’m going to be asking you for links that I can add to the episode notes, by the way for people who can just click on it immediately. And the second thing I wanted to mention was that in the course that we were talking about the Diversity and Inclusion course that we’ve just released, we have paid the people who have very generously shared their expertise and time. Two of the main people who were featured in the course are Amelie Lamont, pronouns ‘they/them’. They are the owner of Amelie Studio. And they’ve done an amazing Guide to Allyship, which we’ve used in the course, and Luckie Alexander, pronouns, he/him/Superman. That’s just a little joke, obviously, but it’s on his social media. It says “Pronouns: he, him and Superman”, and he is the leader of Invisible Men or Invisible Trans Men, and he’s provided a lot of really interesting materials for the course. So I just wanted to mention that we have paid them for their materials or for their time, and we’ll be promoting their work as well going forward. Because while it is extremely important that we educate ourselves, we might want to have conversations with people who are open to it. But we should not expect them to do the work for us, and especially not for free. So by learning, by having conversations with people generally trying to do better by studying this course, you’re going to be able to have more in depth, more valuable, more open-minded conversations with people from those communities. Great. But don’t go out there and expect them to teach you all of these things.

A: Don’t be lazy.

L: It’s your obligation. Yes, exactly. Don’t be lazy. And yeah, and pay people for their time, for their work. Appreciate them, promote them in whatever way they want to be promoted. And yeah, we can all sort of move…

A: …move the needle.

L: Yeah. Normally, I close the podcast by asking my guests, if they have any advice that they would like to share with the listeners, that could be about learning a language, it could be about your field of expertise. It could be anything that you like. Do you have any advice that you’d like to share with our listeners?

A: I think one thing I would like to share, which is probably more to do with my work in Communication, then that D&I but there’s lots of overlap anyway, would be to remember that in the connected world, you’re only ever an email away. A message away from most people. So I think if there’s anything you want to learn anyone you want to connect with, I would always encourage people to do that. Worst case scenario, you don’t get a response. Best case scenario, you can open up the door to a new conversation or a new friendship.

L: 100% I’ve met loads of really cool people lately because of that.

A: Yeah, exactly. So that would be my recommendation.

L: Awesome. That’s good advice. Thank you so much for joining us, Alyssa. I’d love to know how we can find out more about the work that you’re doing right now. Can you tell us a little bit about what we can expect to see from you in the future? And of course, I’ll add links to the episode notes.

A: Yeah, absolutely. Well, some of the work that I’ve been doing in the last year, a lot of the work that I’ve been doing, has been in running workshops. So I’ve done some really fun, exciting work through a company called Hustle Crew, which is where I spend a lot of my time because they just have so much of my passion and respect. They have an incredible founder who I’m thrilled to call my friend, my colleague, Abadesi. And yeah, in the last year, some of the teams we’ve done workshops for have been a lot of teams in the NHS at Brandwatch at Stella McCartney and Skye, Airbnb and Amazon kind of all over the show. We kind of go wherever we’re wanted, whenever there’s a need, because we want to help so I’ve been really excited to do lots of workshops, particularly around bias, and helping train people through giving them real-life scenarios as well. And kind of walking them through those scenarios and saying, okay, you know, “If this conversation happened at a work event…”, or “If you notice this happening in the meeting, you know, what would be the most bold move the most radical move for inclusion you can make in that moment?” And we’ve seen really exciting things come out of that. Oftentimes, by the time we’re brought in, it’s like, so kind of giving people an opportunity to practice in a safe space with a let relatively low emotional cognitive load, because it’s like, not a live situation. But it could be. A kind of helps people think about build confidence when talking about different issues and talking about different identities and things that maybe they might have been previously more accustomed to throwing under the rug, or to your example earlier, just avoiding those people because they’re different from them. And because they’re not used to it, or because they feel some sort of like discomfort. So just really helping people engage with discomfort. Because it’s the only way to get more comfortable. And have more fun with each other. So that’s something I’ve been really excited to work on. And sometimes also, the work that I do in Marketing is usually not related to D&I. But once in a while, the projects converge, I was doing a fun project for a company called Cult Beauty. Because on their platform, they sell everything from Chanel, to Fenty Beauty, you know, like, you can find everything there, it’s great, great little plug for them. But something that we noticed was that on the platform, like when you’re interacting with it, and you’re in their user interface, you can see things like organic products, or sustainable products. And there are so many different environmental tags that they have on the site. So you can search for just ‘eco-friendly products’, for example, if you’re conscious of that. But what they didn’t necessarily have was tagging based on kind of cultural background. So something we put into place was making sure that if you wanted to just buy from a Black-owned business, or female-owned business, or a female Black-owned business, or a business, you know, owned, owned and led by, by people of colour, that that’s something that you can now do. And so to be more intentional about where you’re spending your money, because economic power it makes the world go round, as we know. So those are some of the different kinds of projects that I’ve been working on, I also spend a lot of time contributing to charities that I’m on the board for. Little shout outs to them. One is called My Pickle. And they help people get access to help fast who are in crisis. And another one is called Beyond Equality. And they’re an organisation that works primarily with men and boys, but also with women too, to promote positive masculinity and kind of disrupting the idea that boys will be boys because they only will if we let them. Some of what they’re working on is, of course, to lower, lessen or, you know, outright stop gender-based violence, which is largely male perpetrators, although not exclusively, but also things like the fact that you know, male suicide in the UK is the highest cause of death for men under 48. And a lot of these things are connected. So that’s sort of some of where I spend my time and in terms of how people can connect with me: on LinkedIn. So we can maybe drop a link into under this podcast, wherever it’s gonna live, on your website, if people look for Alyssa Ordu, there’s only one of me, there’s not that many Nigerians out there. So they can connect with you that way. And then we can see whether I can maybe help them with something they might want my kind of support with.

L: Gosh, you are busy, busy person, aren’t you?

A: That’s why she’s on holiday, finally.

L: Yes, and that’s why I’m bothering you when you’re on your holiday. Oh, bless you.

A: You couldn’t bother me if you tried, Lori.

L: Oh, love, bless you so much. I have thoroughly enjoyed our conversation, Alyssa, as always. I can’t believe that was your first podcast!

A: This is my first podcast. Well, I’m really happy it was with you.

L: Oh, thank you.

Thank you so much for being here today for this conversation between Alyssa and I. I love to talk to people about these issues, so if you have any questions about the vocabulary, the topics that we’ve mentioned, or any of the resources that you can find in the episode notes, please drop me a line by opening the chat box at the bottom right-hand corner of any screen on our website.

From everyone at Intrepid English, have a wonderful day.

Resources mentioned during this conversation

Alyssa Ordu on LinkedIn

Article: Covid inspires

1,200 new German words

The Root

Jezebel

Hustle Crew

Lesbians Who Tech

Black Girls Code

amelie. studio

Invisible T Men

Beyond Equality

Cult Beauty

My Pickle

As always, feel free to ask us a question

by clicking on the Chat Box at the bottom of your screen

I agree to call a spade a spade and to address things specifically. But what seems even more important to me is what I discovered on a poster in Italy. I’ll write the original version first, then I’ll try to translate it into English:

“Un grammo di comportamento vale più di un chilo di parole”

One gram of behaviour is worth more than a kilo of words.

What we do matters!

Hi Richard,

Thanks for this thought-provoking message. I completely agree.

Intrepid English is committed to ‘putting our money where our mouth is’ by making a positive impact through our actions.

With a wonderful community like ours, we can make a real difference.

Have a lovely day.

Lorraine